Co-Authored-By: Carol Willing carolcode@willingconsulting.com Co-Authored-By: Ezio Melotti ezio.melotti@gmail.com Co-Authored-By: Hugo van Kemenade hugovk@users.noreply.github.com Co-Authored-By: Itamar Ostricher itamarost@gmail.com Co-Authored-By: Jesús Cea jcea@jcea.es Co-Authored-By: Joannah Nanjekye 33177550+nanjekyejoannah@users.noreply.github.com Co-Authored-By: Ned Batchelder ned@nedbatchelder.com Co-Authored-By: Pablo Galindo Salgado Pablogsal@gmail.com Co-Authored-By: Pamela Fox pamela.fox@gmail.com Co-Authored-By: Sam Gross colesbury@gmail.com Co-Authored-By: Stefan Pochmann 609905+pochmann@users.noreply.github.com Co-Authored-By: T. Wouters thomas@python.org Co-Authored-By: q-ata 24601033+q-ata@users.noreply.github.com Co-Authored-By: slateny 46876382+slateny@users.noreply.github.com Co-Authored-By: Борис Верховский boris.verk@gmail.com Co-authored-by: Adam Turner <9087854+AA-Turner@users.noreply.github.com> Co-authored-by: Jacob Coffee <jacob@z7x.org>

29 KiB

Garbage collector design

Abstract

The main garbage collection algorithm used by CPython is reference counting. The basic idea is

that CPython counts how many different places there are that have a reference to an

object. Such a place could be another object, or a global (or static) C variable, or

a local variable in some C function. When an object’s reference count becomes zero,

the object is deallocated. If it contains references to other objects, their

reference counts are decremented. Those other objects may be deallocated in turn, if

this decrement makes their reference count become zero, and so on. The reference

count field can be examined using the sys.getrefcount() function (notice that the

value returned by this function is always 1 more as the function also has a reference

to the object when called):

>>> x = object()

>>> sys.getrefcount(x)

2

>>> y = x

>>> sys.getrefcount(x)

3

>>> del y

>>> sys.getrefcount(x)

2

The main problem with the reference counting scheme is that it does not handle reference cycles. For instance, consider this code:

>>> container = []

>>> container.append(container)

>>> sys.getrefcount(container)

3

>>> del container

In this example, container holds a reference to itself, so even when we remove

our reference to it (the variable "container") the reference count never falls to 0

because it still has its own internal reference. Therefore it would never be

cleaned just by simple reference counting. For this reason some additional machinery

is needed to clean these reference cycles between objects once they become

unreachable. This is the cyclic garbage collector, usually called just Garbage

Collector (GC), even though reference counting is also a form of garbage collection.

Starting in version 3.13, CPython contains two GC implementations:

- The default build implementation relies on the global interpreter lock for thread safety.

- The free-threaded build implementation pauses other executing threads when performing a collection for thread safety.

Both implementations use the same basic algorithms, but operate on different data structures. The the section on Differences between GC implementations for the details.

Memory layout and object structure

The garbage collector requires additional fields in Python objects to support garbage collection. These extra fields are different in the default and the free-threaded builds.

GC for the default build

Normally the C structure supporting a regular Python object looks as follows:

object -----> +--+--+--+--+--+--+--+--+--+--+--+--+--+--+--+--+ \

| ob_refcnt | |

+--+--+--+--+--+--+--+--+--+--+--+--+--+--+--+--+ | PyObject_HEAD

| *ob_type | |

+--+--+--+--+--+--+--+--+--+--+--+--+--+--+--+--+ /

| ... |

In order to support the garbage collector, the memory layout of objects is altered to accommodate extra information before the normal layout:

+--+--+--+--+--+--+--+--+--+--+--+--+--+--+--+--+ \

| *_gc_next | |

+--+--+--+--+--+--+--+--+--+--+--+--+--+--+--+--+ | PyGC_Head

| *_gc_prev | |

object -----> +--+--+--+--+--+--+--+--+--+--+--+--+--+--+--+--+ /

| ob_refcnt | \

+--+--+--+--+--+--+--+--+--+--+--+--+--+--+--+--+ | PyObject_HEAD

| *ob_type | |

+--+--+--+--+--+--+--+--+--+--+--+--+--+--+--+--+ /

| ... |

In this way the object can be treated as a normal python object and when the extra

information associated to the GC is needed the previous fields can be accessed by a

simple type cast from the original object: ((PyGC_Head *)(the_object)-1).

As is explained later in the Optimization: reusing fields to save memory section, these two extra fields are normally used to keep doubly linked lists of all the objects tracked by the garbage collector (these lists are the GC generations, more on that in the Optimization: generations section), but they are also reused to fulfill other purposes when the full doubly linked list structure is not needed as a memory optimization.

Doubly linked lists are used because they efficiently support the most frequently required operations. In general, the collection of all objects tracked by GC is partitioned into disjoint sets, each in its own doubly linked list. Between collections, objects are partitioned into "generations", reflecting how often they've survived collection attempts. During collections, the generation(s) being collected are further partitioned into, for example, sets of reachable and unreachable objects. Doubly linked lists support moving an object from one partition to another, adding a new object, removing an object entirely (objects tracked by GC are most often reclaimed by the refcounting system when GC isn't running at all!), and merging partitions, all with a small constant number of pointer updates. With care, they also support iterating over a partition while objects are being added to - and removed from - it, which is frequently required while GC is running.

GC for the free-threaded build

In the free-threaded build, Python objects contain a 1-byte field

ob_gc_bits that is used to track garbage collection related state. The

field exists in all objects, including ones that do not support cyclic

garbage collection. The field is used to identify objects that are tracked

by the collector, ensure that finalizers are called only once per object,

and, during garbage collection, differentiate reachable vs. unreachable objects.

object -----> +--+--+--+--+--+--+--+--+--+--+--+--+--+--+--+--+ \

| ob_tid | |

+--+--+--+--+--+--+--+--+--+--+--+--+--+--+--+--+ |

| pad | ob_mutex | ob_gc_bits | ob_ref_local | |

+--+--+--+--+--+--+--+--+--+--+--+--+--+--+--+--+ | PyObject_HEAD

| ob_ref_shared | |

+--+--+--+--+--+--+--+--+--+--+--+--+--+--+--+--+ |

| *ob_type | |

+--+--+--+--+--+--+--+--+--+--+--+--+--+--+--+--+ /

| ... |

Note that not all fields are to scale. pad is two bytes, ob_mutex and

ob_gc_bits are each one byte, and ob_ref_local is four bytes. The

other fields, ob_tid, ob_ref_shared, and ob_type, are all

pointer-sized (that is, eight bytes on a 64-bit platform).

The garbage collector also temporarily repurposes the ob_tid (thread ID)

and ob_ref_local (local reference count) fields for other purposes during

collections.

C APIs

Specific APIs are offered to allocate, deallocate, initialize, track, and untrack objects with GC support. These APIs can be found in the Garbage Collector C API documentation.

Apart from this object structure, the type object for objects supporting garbage

collection must include the Py_TPFLAGS_HAVE_GC in its tp_flags slot and

provide an implementation of the tp_traverse handler. Unless it can be proven

that the objects cannot form reference cycles with only objects of its type or unless

the type is immutable, a tp_clear implementation must also be provided.

Identifying reference cycles

The algorithm that CPython uses to detect those reference cycles is

implemented in the gc module. The garbage collector only focuses

on cleaning container objects (that is, objects that can contain a reference

to one or more objects). These can be arrays, dictionaries, lists, custom

class instances, classes in extension modules, etc. One could think that

cycles are uncommon but the truth is that many internal references needed by

the interpreter create cycles everywhere. Some notable examples:

- Exceptions contain traceback objects that contain a list of frames that contain the exception itself.

- Module-level functions reference the module's dict (which is needed to resolve globals), which in turn contains entries for the module-level functions.

- Instances have references to their class which itself references its module, and the module contains references to everything that is inside (and maybe other modules) and this can lead back to the original instance.

- When representing data structures like graphs, it is very typical for them to have internal links to themselves.

To correctly dispose of these objects once they become unreachable, they need

to be identified first. To understand how the algorithm works, let’s take

the case of a circular linked list which has one link referenced by a

variable A, and one self-referencing object which is completely

unreachable:

>>> import gc

>>> class Link:

... def __init__(self, next_link=None):

... self.next_link = next_link

>>> link_3 = Link()

>>> link_2 = Link(link_3)

>>> link_1 = Link(link_2)

>>> link_3.next_link = link_1

>>> A = link_1

>>> del link_1, link_2, link_3

>>> link_4 = Link()

>>> link_4.next_link = link_4

>>> del link_4

# Collect the unreachable Link object (and its .__dict__ dict).

>>> gc.collect()

2

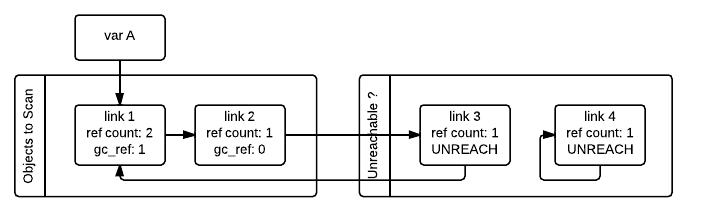

The GC starts with a set of candidate objects it wants to scan. In the default build, these "objects to scan" might be all container objects or a smaller subset (or "generation"). In the free-threaded build, the collector always scans all container objects.

The objective is to identify all the unreachable objects. The collector does this by identifying reachable objects; the remaining objects must be unreachable. The first step is to identify all of the "to scan" objects that are directly reachable from outside the set of candidate objects. These objects have a refcount larger than the number of incoming references from within the candidate set.

Every object that supports garbage collection will have an extra reference

count field initialized to the reference count (gc_ref in the figures)

of that object when the algorithm starts. This is because the algorithm needs

to modify the reference count to do the computations and in this way the

interpreter will not modify the real reference count field.

The GC then iterates over all containers in the first list and decrements by one the

gc_ref field of any other object that container is referencing. Doing

this makes use of the tp_traverse slot in the container class (implemented

using the C API or inherited by a superclass) to know what objects are referenced by

each container. After all the objects have been scanned, only the objects that have

references from outside the “objects to scan” list will have gc_ref > 0.

Notice that having gc_ref == 0 does not imply that the object is unreachable.

This is because another object that is reachable from the outside (gc_ref > 0)

can still have references to it. For instance, the link_2 object in our example

ended having gc_ref == 0 but is referenced still by the link_1 object that

is reachable from the outside. To obtain the set of objects that are really

unreachable, the garbage collector re-scans the container objects using the

tp_traverse slot; this time with a different traverse function that marks objects with

gc_ref == 0 as "tentatively unreachable" and then moves them to the

tentatively unreachable list. The following image depicts the state of the lists in a

moment when the GC processed the link_3 and link_4 objects but has not

processed link_1 and link_2 yet.

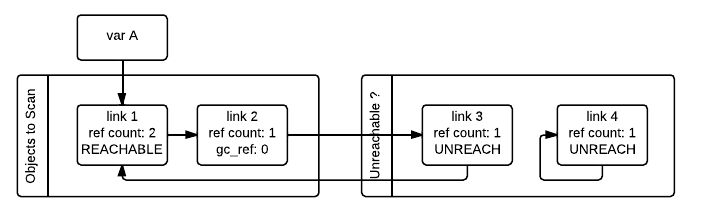

Then the GC scans the next link_1 object. Because it has gc_ref == 1,

the gc does not do anything special because it knows it has to be reachable (and is

already in what will become the reachable list):

When the GC encounters an object which is reachable (gc_ref > 0), it traverses

its references using the tp_traverse slot to find all the objects that are

reachable from it, moving them to the end of the list of reachable objects (where

they started originally) and setting its gc_ref field to 1. This is what happens

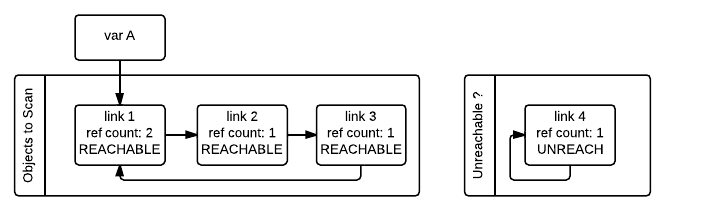

to link_2 and link_3 below as they are reachable from link_1. From the

state in the previous image and after examining the objects referred to by link_1

the GC knows that link_3 is reachable after all, so it is moved back to the

original list and its gc_ref field is set to 1 so that if the GC visits it again,

it will know that it's reachable. To avoid visiting an object twice, the GC marks all

objects that have already been visited once (by unsetting the PREV_MASK_COLLECTING

flag) so that if an object that has already been processed is referenced by some other

object, the GC does not process it twice.

Notice that an object that was marked as "tentatively unreachable" and was later moved back to the reachable list will be visited again by the garbage collector as now all the references that that object has need to be processed as well. This process is really a breadth first search over the object graph. Once all the objects are scanned, the GC knows that all container objects in the tentatively unreachable list are really unreachable and can thus be garbage collected.

Pragmatically, it's important to note that no recursion is required by any of this,

and neither does it in any other way require additional memory proportional to the

number of objects, number of pointers, or the lengths of pointer chains. Apart from

O(1) storage for internal C needs, the objects themselves contain all the storage

the GC algorithms require.

Why moving unreachable objects is better

It sounds logical to move the unreachable objects under the premise that most objects are usually reachable, until you think about it: the reason it pays isn't actually obvious.

Suppose we create objects A, B, C in that order. They appear in the young generation in the same order. If B points to A, and C to B, and C is reachable from outside, then the adjusted refcounts after the first step of the algorithm runs will be 0, 0, and 1 respectively because the only reachable object from the outside is C.

When the next step of the algorithm finds A, A is moved to the unreachable list. The same for B when it's first encountered. Then C is traversed, B is moved back to the reachable list. B is eventually traversed, and then A is moved back to the reachable list.

So instead of not moving at all, the reachable objects B and A are each moved twice. Why is this a win? A straightforward algorithm to move the reachable objects instead would move A, B, and C once each. The key is that this dance leaves the objects in order C, B, A - it's reversed from the original order. On all subsequent scans, none of them will move. Since most objects aren't in cycles, this can save an unbounded number of moves across an unbounded number of later collections. The only time the cost can be higher is the first time the chain is scanned.

Destroying unreachable objects

Once the GC knows the list of unreachable objects, a very delicate process starts with the objective of completely destroying these objects. Roughly, the process follows these steps in order:

- Handle and clear weak references (if any). Weak references to unreachable objects

are set to

None. If the weak reference has an associated callback, the callback is enqueued to be called once the clearing of weak references is finished. We only invoke callbacks for weak references that are themselves reachable. If both the weak reference and the pointed-to object are unreachable we do not execute the callback. This is partly for historical reasons: the callback could resurrect an unreachable object and support for weak references predates support for object resurrection. Ignoring the weak reference's callback is fine because both the object and the weakref are going away, so it's legitimate to say the weak reference is going away first. - If an object has legacy finalizers (

tp_delslot) move it to thegc.garbagelist. - Call the finalizers (

tp_finalizeslot) and mark the objects as already finalized to avoid calling finalizers twice if the objects are resurrected or if other finalizers have removed the object first. - Deal with resurrected objects. If some objects have been resurrected, the GC finds the new subset of objects that are still unreachable by running the cycle detection algorithm again and continues with them.

- Call the

tp_clearslot of every object so all internal links are broken and the reference counts fall to 0, triggering the destruction of all unreachable objects.

Optimization: generations

In order to limit the time each garbage collection takes, the GC implementation for the default build uses a popular optimization: generations. The main idea behind this concept is the assumption that most objects have a very short lifespan and can thus be collected soon after their creation. This has proven to be very close to the reality of many Python programs as many temporary objects are created and destroyed very quickly.

To take advantage of this fact, all container objects are segregated into three spaces/generations. Every new object starts in the first generation (generation 0). The previous algorithm is executed only over the objects of a particular generation and if an object survives a collection of its generation it will be moved to the next one (generation 1), where it will be surveyed for collection less often. If the same object survives another GC round in this new generation (generation 1) it will be moved to the last generation (generation 2) where it will be surveyed the least often.

The GC implementation for the free-threaded build does not use multiple generations. Every collection operates on the entire heap.

In order to decide when to run, the collector keeps track of the number of object

allocations and deallocations since the last collection. When the number of

allocations minus the number of deallocations exceeds threshold_0,

collection starts. Initially only generation 0 is examined. If generation 0 has

been examined more than threshold_1 times since generation 1 has been

examined, then generation 1 is examined as well. With generation 2,

things are a bit more complicated; see

Collecting the oldest generation for

more information. These thresholds can be examined using the

gc.get_threshold()

function:

>>> import gc

>>> gc.get_threshold()

(700, 10, 10)

The content of these generations can be examined using the

gc.get_objects(generation=NUM) function and collections can be triggered

specifically in a generation by calling gc.collect(generation=NUM).

>>> import gc

>>> class MyObj:

... pass

...

# Move everything to the last generation so it's easier to inspect

# the younger generations.

>>> gc.collect()

0

# Create a reference cycle.

>>> x = MyObj()

>>> x.self = x

# Initially the object is in the youngest generation.

>>> gc.get_objects(generation=0)

[..., <__main__.MyObj object at 0x7fbcc12a3400>, ...]

# After a collection of the youngest generation the object

# moves to the next generation.

>>> gc.collect(generation=0)

0

>>> gc.get_objects(generation=0)

[]

>>> gc.get_objects(generation=1)

[..., <__main__.MyObj object at 0x7fbcc12a3400>, ...]

Collecting the oldest generation

In addition to the various configurable thresholds, the GC only triggers a full

collection of the oldest generation if the ratio long_lived_pending / long_lived_total

is above a given value (hardwired to 25%). The reason is that, while "non-full"

collections (that is, collections of the young and middle generations) will always

examine roughly the same number of objects (determined by the aforementioned

thresholds) the cost of a full collection is proportional to the total

number of long-lived objects, which is virtually unbounded. Indeed, it has

been remarked that doing a full collection every of object

creations entails a dramatic performance degradation in workloads which consist

of creating and storing lots of long-lived objects (for example, building a large list

of GC-tracked objects would show quadratic performance, instead of linear as

expected). Using the above ratio, instead, yields amortized linear performance

in the total number of objects (the effect of which can be summarized thusly:

"each full garbage collection is more and more costly as the number of objects

grows, but we do fewer and fewer of them").

Optimization: reusing fields to save memory

In order to save memory, the two linked list pointers in every object with GC

support are reused for several purposes. This is a common optimization known

as "fat pointers" or "tagged pointers": pointers that carry additional data,

"folded" into the pointer, meaning stored inline in the data representing the

address, taking advantage of certain properties of memory addressing. This is

possible as most architectures align certain types of data

to the size of the data, often a word or multiple thereof. This discrepancy

leaves a few of the least significant bits of the pointer unused, which can be

used for tags or to keep other information – most often as a bit field (each

bit a separate tag) – as long as code that uses the pointer masks out these

bits before accessing memory. For example, on a 32-bit architecture (for both

addresses and word size), a word is 32 bits = 4 bytes, so word-aligned

addresses are always a multiple of 4, hence end in 00, leaving the last 2 bits

available; while on a 64-bit architecture, a word is 64 bits = 8 bytes, so

word-aligned addresses end in 000, leaving the last 3 bits available.

The CPython GC makes use of two fat pointers that correspond to the extra fields

of PyGC_Head discussed in the Memory layout and object structure_ section:

Warning

Because the presence of extra information, "tagged" or "fat" pointers cannot be dereferenced directly and the extra information must be stripped off before obtaining the real memory address. Special care needs to be taken with functions that directly manipulate the linked lists, as these functions normally assume the pointers inside the lists are in a consistent state.

-

The

_gc_prevfield is normally used as the "previous" pointer to maintain the doubly linked list but its lowest two bits are used to keep the flagsPREV_MASK_COLLECTINGand_PyGC_PREV_MASK_FINALIZED. Between collections, the only flag that can be present is_PyGC_PREV_MASK_FINALIZEDthat indicates if an object has been already finalized. During collections_gc_previs temporarily used for storing a copy of the reference count (gc_ref), in addition to two flags, and the GC linked list becomes a singly linked list until_gc_previs restored. -

The

_gc_nextfield is used as the "next" pointer to maintain the doubly linked list but during collection its lowest bit is used to keep theNEXT_MASK_UNREACHABLEflag that indicates if an object is tentatively unreachable during the cycle detection algorithm. This is a drawback to using only doubly linked lists to implement partitions: while most needed operations are constant-time, there is no efficient way to determine which partition an object is currently in. Instead, when that's needed, ad hoc tricks (like theNEXT_MASK_UNREACHABLEflag) are employed.

Optimization: delay tracking containers

Certain types of containers cannot participate in a reference cycle, and so do not need to be tracked by the garbage collector. Untracking these objects reduces the cost of garbage collection. However, determining which objects may be untracked is not free, and the costs must be weighed against the benefits for garbage collection. There are two possible strategies for when to untrack a container:

- When the container is created.

- When the container is examined by the garbage collector.

As a general rule, instances of atomic types aren't tracked and instances of non-atomic types (containers, user-defined objects...) are. However, some type-specific optimizations can be present in order to suppress the garbage collector footprint of simple instances. Some examples of native types that benefit from delayed tracking:

-

Tuples containing only immutable objects (integers, strings etc, and recursively, tuples of immutable objects) do not need to be tracked. The interpreter creates a large number of tuples, many of which will not survive until garbage collection. It is therefore not worthwhile to untrack eligible tuples at creation time. Instead, all tuples except the empty tuple are tracked when created. During garbage collection it is determined whether any surviving tuples can be untracked. A tuple can be untracked if all of its contents are already not tracked. Tuples are examined for untracking in all garbage collection cycles. It may take more than one cycle to untrack a tuple.

-

Dictionaries containing only immutable objects also do not need to be tracked. Dictionaries are untracked when created. If a tracked item is inserted into a dictionary (either as a key or value), the dictionary becomes tracked. During a full garbage collection (all generations), the collector will untrack any dictionaries whose contents are not tracked.

The garbage collector module provides the Python function is_tracked(obj), which returns

the current tracking status of the object. Subsequent garbage collections may change the

tracking status of the object.

>>> gc.is_tracked(0)

False

>>> gc.is_tracked("a")

False

>>> gc.is_tracked([])

True

>>> gc.is_tracked({})

False

>>> gc.is_tracked({"a": 1})

False

>>> gc.is_tracked({"a": []})

True

Differences between GC implementations

This section summarizes the differences between the GC implementation in the default build and the implementation in the free-threaded build.

The default build implementation makes extensive use of the PyGC_Head data

structure, while the free-threaded build implementation does not use that

data structure.

- The default build implementation stores all tracked objects in a doubly

linked list using

PyGC_Head. The free-threaded build implementation instead relies on the embedded mimalloc memory allocator to scan the heap for tracked objects. - The default build implementation uses

PyGC_Headfor the unreachable object list. The free-threaded build implementation repurposes theob_tidfield to store a unreachable objects linked list. - The default build implementation stores flags in the

_gc_prevfield ofPyGC_Head. The free-threaded build implementation stores these flags inob_gc_bits.

The default build implementation relies on the global interpreter lock for thread safety. The free-threaded build implementation has two "stop the world" pauses, in which all other executing threads are temporarily paused so that the GC can safely access reference counts and object attributes.

The default build implementation is a generational collector. The free-threaded build is non-generational; each collection scans the entire heap.

- Keeping track of object generations is simple and inexpensive in the default build. The free-threaded build relies on mimalloc for finding tracked objects; identifying "young" objects without scanning the entire heap would be more difficult.

Note

Document history

Pablo Galindo Salgado - Original author

Irit Katriel - Convert to Markdown